Jan 18, 2019

A top-performing U.S. hedge fund is shorting Canada's banks

, Bloomberg News

A small U.S. hedge fund that was a top performer last year is shorting Canadian banks.

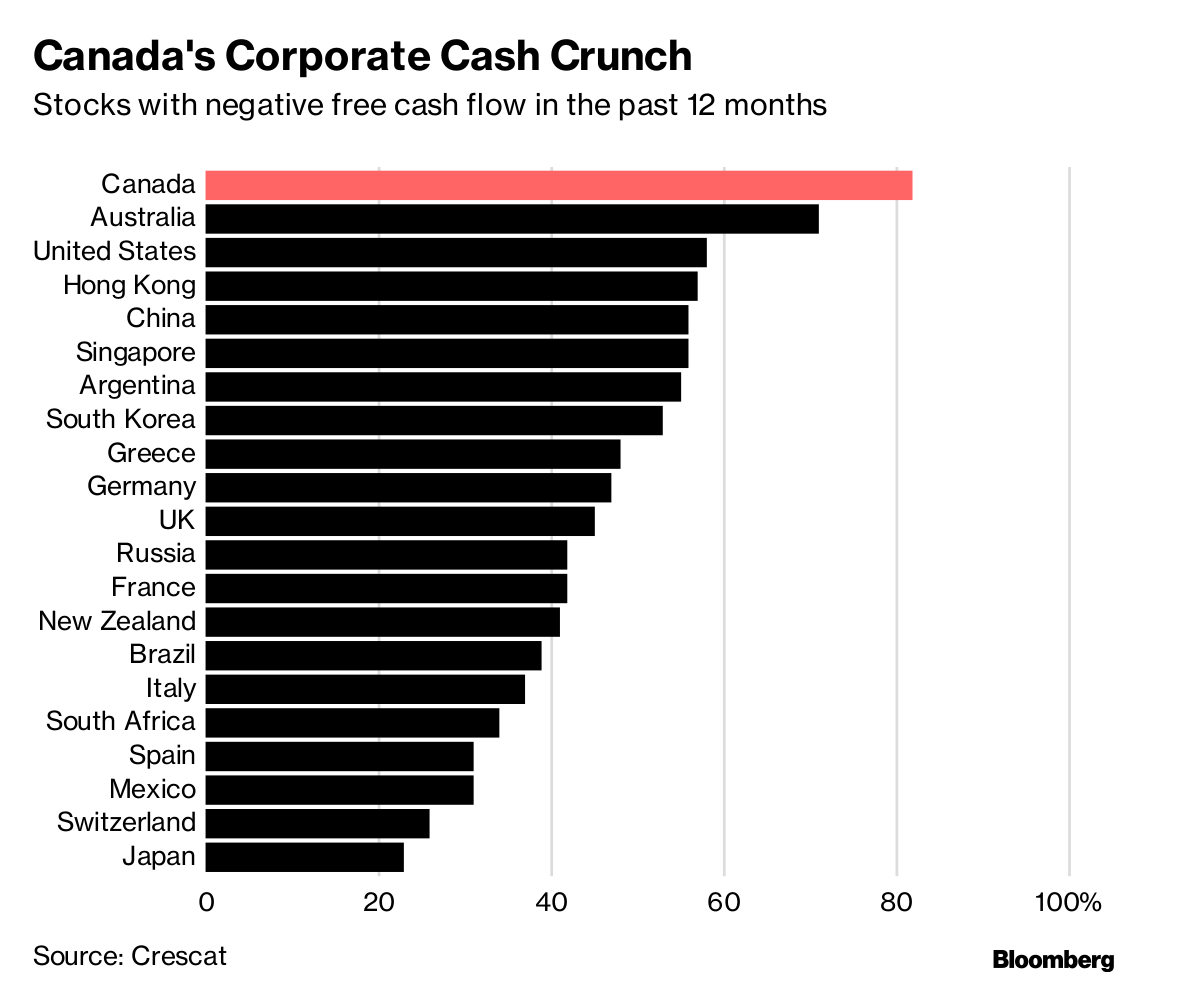

Crescat Capital sees the Canadian economy heading for recession as the housing market buckles. That might be bad enough for the banks but they face an added strain: outside the financial sector, more than 80 per cent of Canadian companies aren’t generating enough cash to support their businesses, the highest in the world, according to Crescat.

“Canadian banks will be left holding the bag and the ones to suffer from what is likely to be a major economic recession,” Tavi Costa, a global macro analyst at Denver-based Crescat, said by phone.

Crescat has only US$55 million under management, but it returned 41 per cent in its Global Macro Fund last year and 32 per cent in its Long/Short Fund, bolstered by a short wager on China, according to its website. That put the company among the top performers in a year in which the industry saw its biggest loss since 2011, declining 4.1 per cent, according to Hedge Fund Research Inc.

The country’s biggest lenders are Royal Bank of Canada and Toronto-Dominion Bank, along with Bank of Nova Scotia, Bank of Montreal, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce and National Bank of Canada. Costa declined to name the banks Crescat was shorting. Representatives for Canada’s six biggest banks didn’t immediately comment or declined to comment.

Crescat’s short comes amid long-standing warnings from economists, investors and even the Bank of Canada about elevated consumer debt, which was driven higher by a decades-long housing boom. Canada’s ratio of household debt to income has been hovering at about 175 per cent for the past two years, compared with a peak of about 134 per cent in the U.S. at the height of its housing bubble in 2007.

Now Canada’s housing market is beginning to cool. Sales plunged 32 per cent in Vancouver last year and 16 percent in Toronto amid rising interest rates, stricter mortgage rules and new taxes.

“China is in the process of reversing its key role as a driver of global economic growth,” the 29-year-old Costa said. “Countries like Canada and Australia, and their respective housing markets, are the economies most vulnerable in this scenario.”

Meanwhile, Crescat calculates that about 80 percent of Canadian non-financial stocks have been cash-flow negative in the past 12 months, which he measures as cash flow from operations minus capital expenditures.

That may be inflated by the the large numbers of “zombie” companies on Canadian stock exchanges, which the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines as those 10 years and older and whose earnings aren’t high enough to cover interest payments on their debts. In a September study, Deloitte found 16 percent of public companies on the Toronto Stock Exchange and its sister Venture Exchange are considered zombies, compared with 10 percent globally.

Cash flow in the energy sector may have been hammered by a slump in crude prices in the past year.

But Costa said even if he excludes energy and materials stocks, 70 percent of Canadian stocks have still lost money on a free cash-flow basis. If you consider only non-financial stocks with a market value of more than $100 million, the share is still more than 50 percent, he said.

“How is it sustainable for companies that generate no cash continue to employ people?" Costa said. "Many of these troubled companies would be bankrupt under tighter monetary conditions.”

Previous Shorts

The country’s biggest lenders could face troubles on both the housing and corporate fronts, according to Costa.

At their peak last year, the six largest banks, traded at an average of 1.9 times book value, a similar valuation to U.S. banks prior to the global financial crisis in 2008, according to Costa. He expects that to drop to 0.7 times book value or so, where U.S. banks were trading post-financial crisis.

Other investors have recommended shorting Canadian financials on a looming housing correction in the past, including Steve Eisman, who predicted the U.S. subprime mortgage collapse.

And Canadians bank stocks have largely defied naysayers as the country’s unemployment rate has hovered near records lows amid steady growth -- until recently. The S&P/TSX Composite Commercial Banks Index slumped 11 percent last year amid market global volatility, the biggest decline since 2008.

"Most of these banks are off their highs and have just started to break down," Costa said.

--With assistance from Doug Alexander and Brandon Kochkodin.

VOTE