One of the biggest questions hanging over Canada’s record household debt is just how much borrowers owe against their homes.

Officials have warned about the dangers of HELOCs -- home equity lines of credit -- and the potential risks to Canada’s financial system. Yet for those seeking to quantify those risks, obtaining a precise figure for Canadian HELOC debt can be tricky.

Regulators agree. That’s why this month the Bank of Canada will begin collecting more detailed data on HELOCs to bolster its analysis of financial-system threats. The central bank has been working informally with lenders on the reporting, which becomes a formal requirement as of May 15.

HELOCs can add to debt burdens because they don’t typically have a fixed repayment schedule. If home prices fall, borrowers can find themselves with more debt than their properties are worth, the dreaded “negative equity” scenario that played a significant role in the U.S. housing crash a decade ago. The issue has come into focus as Canada’s ratio of debt to disposable income reached a record 174 per cent in the fourth quarter.

“Given the flexibility HELOCs can provide, borrowers can use them even in a downturn or if they lost their jobs to sustain household spending and continue to service their other debt,” Robert Colangelo at credit rating company DBRS Ltd. said in a phone interview. “It makes it difficult for lenders to identify emerging credit problems.’’

Less Risky

One obstacle to getting a clear picture is that HELOCs themselves are evolving.

Traditional HELOCs are essentially revolving lines of credit that allow homeowners to borrow up to 65 per cent of their home’s value. The interest rate is usually tied to the prime lending rate, and only the interest on the loan needs to be paid each month. To qualify for a HELOC, the borrower must have at least 20 per cent home equity.

Newer products combine a HELOC with a mortgage. These allow borrowers to tap as much as 80% of the home’s value. A maximum of 65 per cent can be withdrawn on a revolving basis -- the HELOC portion -- while a minimum of 15 per cent must be amortizing, meaning regular payments of principal and interest, similar to a mortgage.

Hybrids Expanding

Growth in stand-alone HELOCs has been flat, while all of the banks are seeing strong growth in the hybrid product, which is relatively less risky because it’s partly amortizing, according to Himanshu Bakshi, credit research analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence in New York. However, these hybrid HELOCs are more complex than traditional ones, he said.

Here’s what we do know.

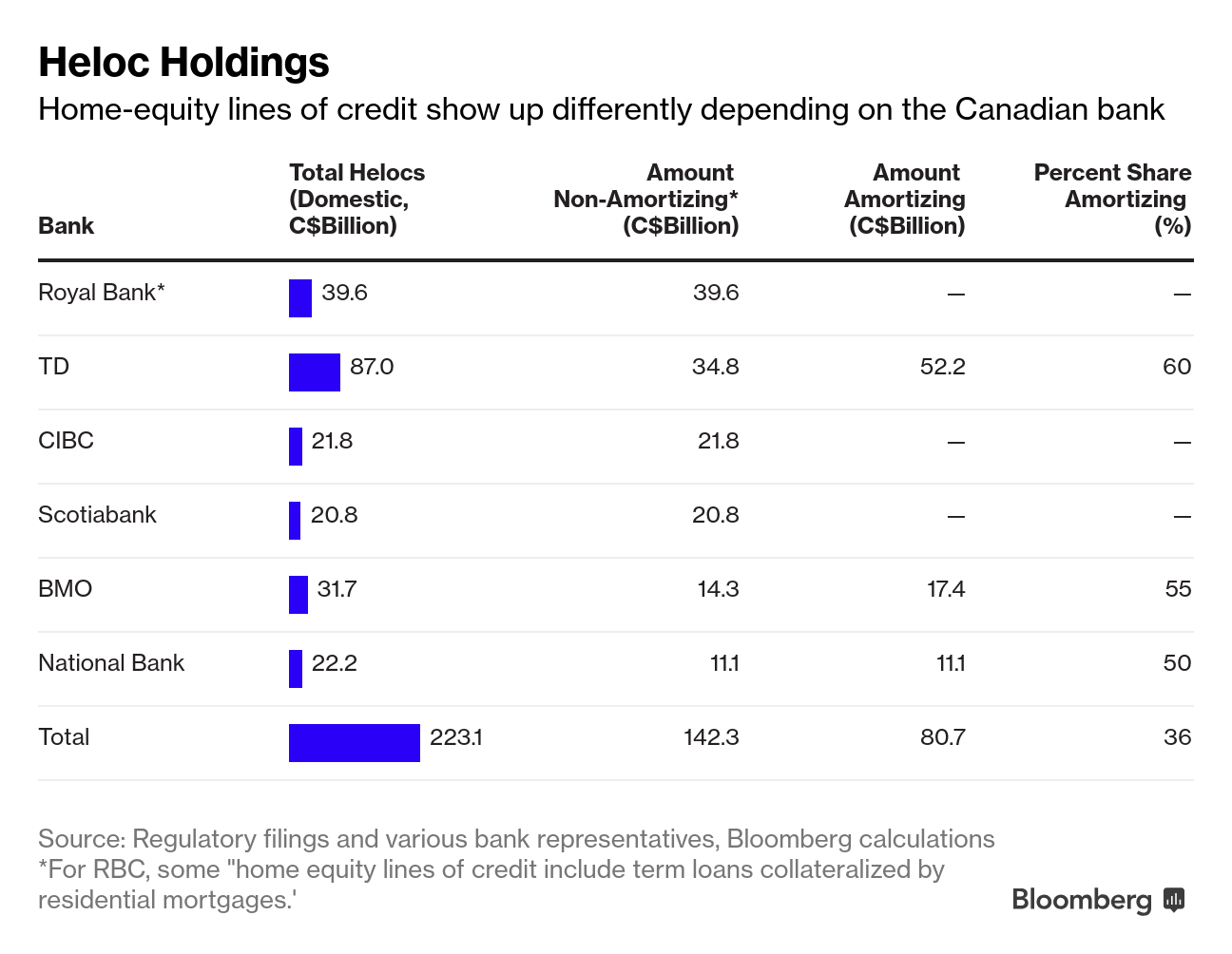

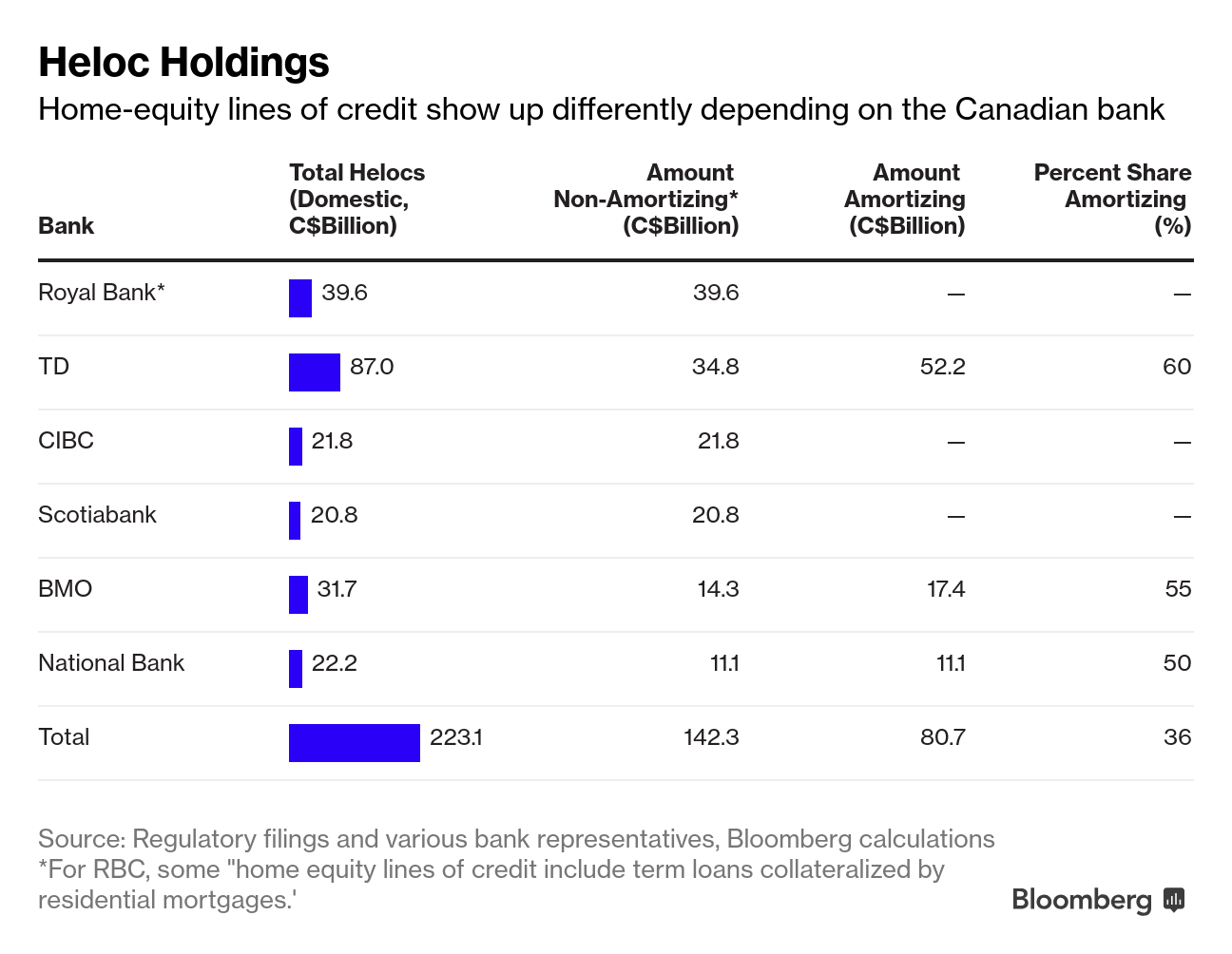

Canada’s six biggest banks reported $223 billion of outstanding, or drawn, HELOCs as of Jan. 31. That accounted for about a tenth of the country’s $2.17 trillion total household debt.

But the banks don’t disclose Heloc balances in the same way. The following was reported in regulatory filings or confirmed by representatives of the banks:

- Toronto-Dominion Bank reported $87 billion of HELOCs. However, it said 60 per cent of that, or $52.2 billion, was the amortizing portion of its blended HELOC-mortgage product, with the remaining $34.8 billion non-amortizing.

- Royal Bank of Canada reported $39.6 billion of non-amortizing HELOCs. A spokeswoman said the bank’s amortizing home equity product is classified as a mortgage. The bank said in a filing that ‘home equity lines of credit include term loans collateralized by residential mortgages.’

- Similarly, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce doesn’t disclose the breakdown of amortizing versus non-amortizing balances for its hybrid product. It reported $21.8 billion in non-amortizing HELOCs.

- Bank of Nova Scotia reported $20.8 billion in HELOCs, which only includes non-amortizing balances. Amortizing balances are reported under residential mortgages.

- Bank of Montreal reports similarly to Toronto-Dominion. A spokesman said 55 per cent, or $17.4 billion of its $31.7 billion in HELOCs was amortizing, while the rest, $14.3 billion, was non-amortizing.

- National Bank of Canada reported $22.2 billion of HELOCs, half of which are amortizing and the other half non-amortizing, according to a spokesman.

One of the major concerns about non-amortizing HELOCs is the possibility for borrowers to pay only the monthly interest due on the loan. A recent government report found about a quarter of Heloc borrowers routinely make interest-only payments.

However, some lenders put that figure much lower. Toronto-Dominion said less than 14% of its Heloc customers made interest-only payments in the past year. RBC said 7 per cent of clients for its Homeline Heloc product make only the scheduled interest payment. None of the other banks disclose that figure.

According to a document on the website of Canada’s Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, the central bank will require a more detailed breakdown of HELOCs, as well as the utilization rate, or the share of drawn amounts versus approved amounts.

The HELOC data will feed into the central bank’s analysis of financial system vulnerabilities and risks, spokeswoman Louise Egan said in an email. In efforts to balance transparency, confidentiality and quality, “data identifying an individual institution will not be published,” she said.

Toronto-Dominion Bank and Scotiabank declined to comment on the new reporting requirements, while CIBC, BMO and National Bank didn’t respond to an email seeking comment. A Royal Bank representative said only the bank would comply with the regulations.

--With assistance from Paul Gulberg, Himanshu Bakshi and Doug Alexander