Jan 24, 2020

Biggest deals of 2019 had BlackRock, Vanguard on both sides

, Bloomberg News

Overlapping ownership in companies participating in some of last year’s biggest mergers and acquisitions may be prodding regulators to pose a new set of questions.

The Federal Trade Commission is asking businesses that seek to merge to identify who their largest shareholders are, reveal what communications they’ve had and show how much influence they exert, Bloomberg News reported this week. The new line of inquiry could add another hurdle to regulatory approval for mergers.

The interest comes as academics and economists raise concerns about the world’s largest asset managers — BlackRock Inc., Vanguard Group Inc. and State Street Corp. — and their growing power in corporate America.

The stakes held by the so-called Big Three fund managers give them an increasingly important voice inside the companies whose shares they own. But the big question is whether that’s harming competition: Do corporate executives engage in more mergers, invest less in R&D, fail to expand capacity or otherwise compete less aggressively because their largest shareholders — the index fund companies — prefer it?

The sheer size of index fund houses merits regulatory attention, said James Woolery, a partner at King & Spalding, where he leads the M&A and corporate governance practices. Though he did not comment specifically on the FTC, he said concentration of power among the three firms deserves more scrutiny.

“That is the issue regulators need to deal with, across regimes,” he said.

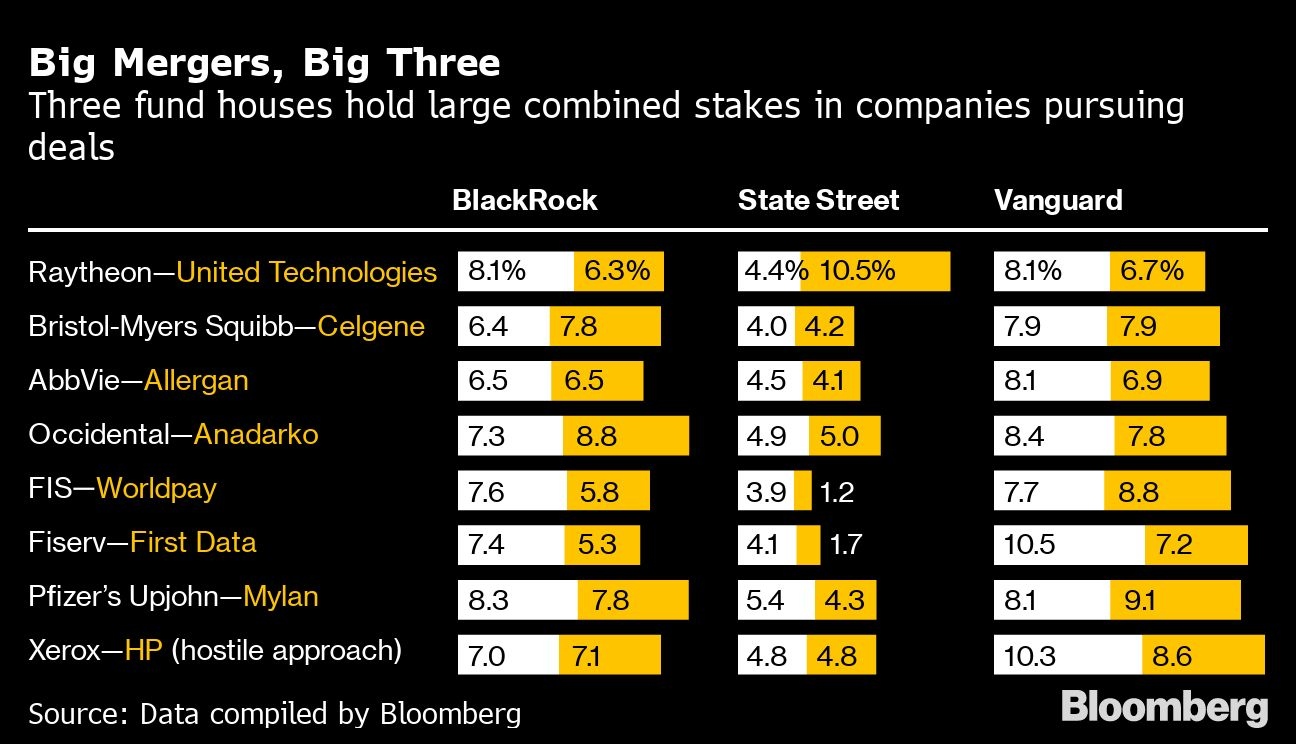

Take some of the largest proposed mergers of the past year: The Big Three, at the time the deals were announced, on average owned about 20 per cent of the acquiring companies and their targets.

For example, when Raytheon Co. and United Technologies Corp. announced their merger, BlackRock held about 8.1 per cent of the former and 6.3 per cent of the latter, while Vanguard owned 8.1 per cent and 6.7 per cent, respectively, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. State Street’s stake was 4.4 per cent and 10.5 per cent, the data show.

The asset managers argue those holdings don’t come close to tipping the outcomes of mergers. They say their influence is overstated because they don’t cast votes as a bloc, and also highlight the difference between a company’s largest shareholders — which could add up to a relatively small stake — and a controlling shareholder that owns a majority of shares.

Some academics, however, have found that existing levels of common ownership increase the likelihood of companies merging and reduce the premiums that sellers receive. The authors conclude that cross-ownership gives the acquirers in deals an information advantage about their targets’ true value. And the parties involved have “superior two-sided information” compared with those who operate only on one side of the deal.

The FTC questions could help antitrust enforcers understand companies’ motives for doing deals. It may also yield more information about how index fund companies wield their influence, said Erik Gordon, clinical assistant professor at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business.

“That is why the FTC is asking about communications between asset managers and their portfolio companies,” he said. “If the FTC finds a push, or even a nudge, it could make a case.”

—With assistance from Denise Cochran and Chloe Whiteaker.