Dec 20, 2019

How a decade of indebtedness is leaving Canadians at 'peak risk'

By Greg Bonnell

'People are hitting the wall': Insolvencies surge as Canadians pushed to the brink

Canadian households are devoting a record amount of their disposable income to making payments on their debt.

It’s just one measure of how the cheap money meant to save us from the financial crisis has resulted in a decade of indebtedness.

The stage was set as central bankers began aggressively cutting borrowing costs in late 2007 to encourage spending as a teetering financial system drove the economy into recession.

It worked – the encouragement to spend, that is. Canadian households have largely carried the economy on their backs for the last decade as the housing market and consumer spending became key pillars of growth.

The numbers, as they say, speak for themselves.

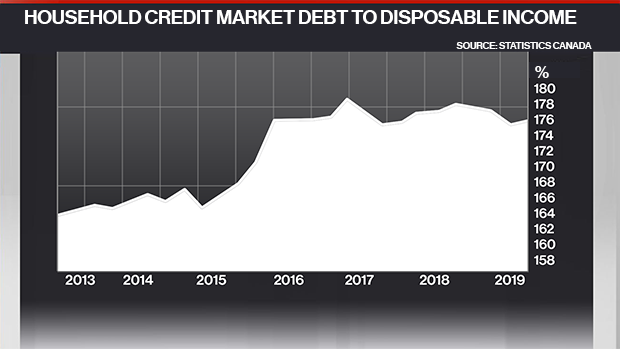

The average Canadian household owes $1.76 for every $1 of annual disposable income.

The same household devotes 15 cents of every disposable dollar to making principal and interest payments on debt – a record high.

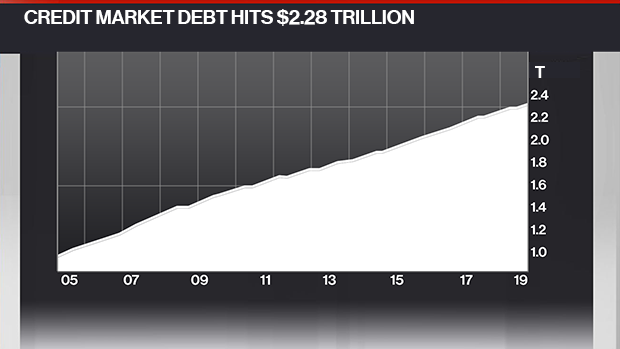

When you add together consumer credit, mortgage and non-mortgage loans, Canadians are carrying $2.28 trillion in credit market debt – and $1.49 trillion of that is mortgage debt.

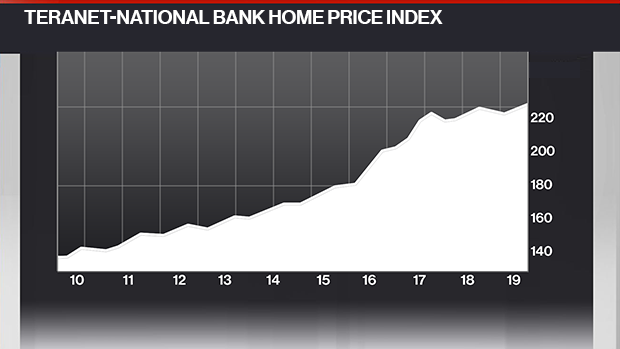

The average price of a home in Canada’s largest real estate market – the Greater Toronto Area – was $395,460 in 2009. Fast forward to 2019 and prices have more than doubled to a year-to-date average price of $818,386. Canada-wide, the Teranet-National Bank Home Price Index has skyrocketed from an index level of 132 in October 2009 to 228 in October 2019 (June 2005 = 100).

As the decade draws to a close, BNN Bloomberg asked several of our regular guests the same question (albeit through the lens of their particular profession): Where has a decade of cheap money left the average Canadian?

Here’s what they said.

--

“It has left us with a wider gap between the haves and the have-nots in Canada. Those who owned or bought a home in the early part of the past decade saw their house values soar… These Canadians are significantly better off than they were a decade ago. Those who do not own a house are worse off than they were a decade ago. Rents have soared over the past decade… A much bigger share of a renter's paycheque is going toward housing costs today, which has also had a negative effect on their savings. This combined with rising home and condo prices have made it even harder for people to buy their first home.” – John Pasalis, president, Realosophy Realty

--

“Low interest rates have been great for the economy and politicians, but terrible for consumers’ financial well-being. The Financial Consumer Agency of Canada reports that HELOCs (Home Equity Lines of Credit) have increased by 40 per cent since 2011, the same percentage do not make regular payments to their principal, and 25 per cent make interest-only payments. This caused the commissioner to warn Canadians to stop using their home as an ATM.

What we’ve learned along the way is that haphazard spending, while lacking a plan to pay it off, can affect your health, work and state of mind… The result is Canadians losing sleep about their money woes, millennials lying about their finances and more employees using work time to deal with financial strains.” - Kelley Keehn, consumer advocate, FP Canada

--

“For the past decade, Canadians have been using credit to balance their budgets. Annual wages for most people have not risen as fast as their living costs. Build in the dramatic rise in rental rates and mortgage payments we’ve seen in the last year or two, and we have a perfect storm of debt risk.

Non-homeowners are already starting to break under the weight of the debt they are carrying. With no assets to refinance, they are increasingly filing for insolvency. Insolvency rates across Canada have already increased to levels not seen since the last recession.

For homeowners, they have a buffer in the form of rising house equity. The next decade looks precarious. High debt equals high risk, and we seem to be at peak risk as we close out the decade. - Scott Terrio, manager of consumer insolvency, Hoyes, Michalos and Associates

--

“Where does this leave the economy? Well, certainly more sensitive to interest rate changes - both on the upside and the downside (and I think the latter is an important point; that is, that even small rate cuts could eventually help more than in the past).

The good news is, of course, that long-term borrowing costs are far below where they were before the 2008/09 recession, and the economy is able to manage much higher levels of debt. Just as one stark example, Ottawa’s debt-service costs in the past year were $24 billion, or just over one per cent of GDP. In 2007, those figures stood at $33 billion and 2.1 per cent of GDP. So even with a larger debt, the burden of servicing that debt has been chopped in half, thanks to sustained lower borrowing costs.

For households, the story isn’t quite as friendly, but debt-service ratios of 14.9 per cent are not much different from the 13.5-to-14.5 per cent range seen late last decade.” – Douglas Porter, chief economist, BMO Financial Group