Jun 19, 2017

Larry Berman: Why the Federal Reserve is bad for America

By Larry Berman

Last week we looked at the meaning behind the flattening yield curve. Despite the fact that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised rates last week and was more hawkish than expected, longer-term bond yields actually declined versus the conventional wisdom that tightening Fed policy should be pushing the entire yield curve higher. At the same time, the FOMC told us that they will likely start to reduce holdings of Treasury and MBS securities from their balance sheet by not repurchasing maturing securities. The Fed expects to begin the normalization of their balance sheet. i.e. unwinding quantitative easing.

Quantitative easing, the buying of large amount of debt to artificially manipulate longer-term interest rates and “quasi” monetize debt, has probably done more harm than good. Those of you looking for safe low volatility returns in your retirement portfolios know what I mean. The yield to maturity of the world bond market is less than two per cent.

This week’s guest, Danielle DiMartino Booth, was recruited to be a research analyst for the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank after her time on Wall Street. Danielle has a critical view of the Fed and the academic elite with no real-world market experience that run it. In her highly-recommended book, Fed Up , Danielle explains what really happened to the U.S. economy after the fateful date of December 8, 2008, when the FOMC approved a grand and unprecedented experiment: lowering interest rates to zero and flooding America with easy money.

From Danielle’s website:

“Until September 2008, when all hell broke loose in a worldwide panic that completely blindsided and, embarrassed the Federal Reserve. The Fed had used billions of dollars in taxpayer funds to bail out Wall Street fat cats. Everyone blamed the Fed.

Just before 9 a.m., the door to the chairman’s office opened. Federal Re- serve Chairman Ben Bernanke took his place in an armchair at the center of a massive oval table. The members of the FOMC found their designated places around the table; aides sat in chairs or couches against the wall. With staff, the room contained fifty or sixty people, far more than normal for this momentous occasion.

In front of each FOMC member was a microphone to record their words for posterity. To a casual observer, the content of their conversation would be obscured by economic jargon.

This day, their essential task was to vote on whether to take the “fed funds” rate—the interest rate at which banks lent money to each other in the overnight market—to the zero bound. The history-making low rate would ripple throughout the economy, affecting the price to borrow for businesses and consumers alike.

Bernanke was calm but insistent. His lifetime of study of the Great Depression indicated this was the only way. His sheer depth of knowledge about the Fed’s mishandling of that tragic period was undoubtedly intimidating.

By the end of the meeting, the vote was unanimous. The FOMC officially adopted a zero-interest-rate policy in the hopes that companies teetering on the brink of insolvency would keep the lights on, keep employees on their payrolls, and keep consumers spending. It would even pay banks interest on deposits.

Free cash. We’ll even pay you to take it!

As they gathered their belongings, everyone shook hands, all very collegial despite the sometimes vigorous discussion. They journeyed back to their nice homes in the toniest neighborhoods of America’s richest cities: New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Dallas, San Francisco, Washington, DC.

They returned to their lofty perches, some at the Eccles Building, others to the executive floors of Federal Reserve District Bank buildings, safely cushioned from the decision they had just made. Most of them were wealthy or had hefty defined benefit pensions. Their investments were socked away in blind trusts. They would feel no pain in their ivory towers.

It took a few months, but the Fed’s mouth-to-mouth resuscitation brought gasping investment banks and hedge funds and giant corporations back to life. Wall Street rejoiced.

But the Fed’s academic models never addressed one basic question: What happens to everyone else?

In the decade following that fateful day, everyday Americans began to suffer the after effects of the Fed’s decision. By 2016, the interest rate still sat at the zero bound, and the Fed’s balance sheet had ballooned to $4.5 trillion, thanks to the Fed’s “quantitative easing” (QE), the label given its continuing purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities.

To what end? All around are signs of an economy frozen in motion thanks to the Fed’s bizarre manipulations of monetary policy, all intended to keep the economy afloat.

The direct damage inflicted on our citizenry begins with our youngest minds and scales up to every living generation in our country’s midst.”

Danielle suggests that Congress should remove the Fed’s dual mandate and take away their goal of job creation and simply make sure they regulate banks and stabilize inflation.

I asked Danielle in a conversation last week if she thought the Fed could actually normalize interest rates? NO! Was her answer. The Fed’s long-term dot plot suggests they think their maximum rate will be 3.00 per cent by 2019. Danielle doubts that they will be able to raise rates much more than they have already. I have a similar viewpoint. It’s part of the lower-for-longer theme I’ve discussed over the past few years. She also doubts they will be able to shrink their balance sheet too much. A lot will depend on Chinese and other central bank foreign reserves and who will be the buyer of that debt.

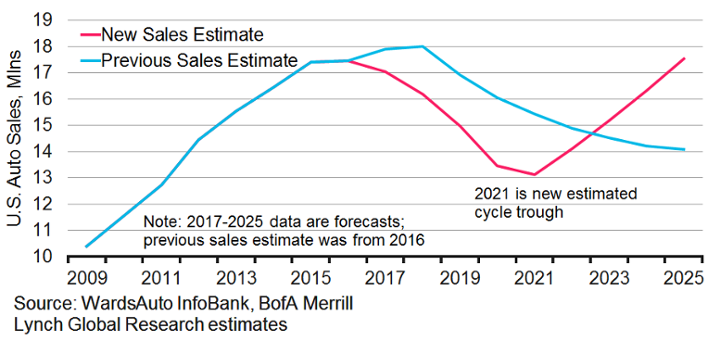

She is very concerned about the downturn in the auto industry and the rising delinquencies on sub-prime auto loans. Interest rates have barely moved up and already millions of Americans are having difficulty making their car loan payments. An industry forecast from BofA Merrill Lynch projects rapidly falling sales through 2021.

She also noted that in May for the first time in years, the U.S. saw a buyer’s market in housing. She is concerned about retailers like Macy’s closing stores that are actually profitable.

Any one of these things could be a catalyst for the next recession.

What policies are the Fed likely to employ during the next recession? If Yellen is nominated for another term, odds are good that we could see negative rates in the U.S. and an even bigger balance sheet further distorting the spread between the haves and have nots.

Danielle writes an excellent weekly blog that you can follow here. She is quite a gifted writer in addition to a very thoughtful analyst. I’ve been reading her weekly blog for the past year and always find it insightful. You should consider following her too.

Follow Larry Online:

Twitter: @LarryBermanETF

LinkedIn Group: ETF Capital Management

Facebook: ETF Capital Management

Web: www.etfcm.com