Apr 19, 2024

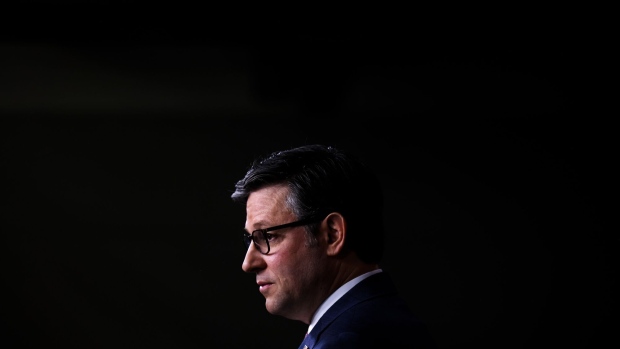

Ultra Conservative Mike Johnson Counts on Democrats for His Survival

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Ukraine’s fate and perhaps even the security of Europe hinge on a man who six months ago was best known for his deep social conservatism, his evangelical Christian faith and his fierce defense of Donald Trump after the former president lost the 2020 election.

Billions of dollars of desperately needed Ukraine aid depend on US House Speaker Mike Johnson’s resolve this weekend in pushing through a complex foreign assistance plan, which also includes help for Israel and a provision forcing China-based Bytedance Ltd. to divest its popular TikTok social media platform.

That will involve the type of complicated political maneuvers and deal-making with Democrats that roil many rank-and-file Republicans.

Before he was speaker, Johnson had the luxury of taking political positions at odds with party leaders, including a stance against new funding for Kyiv. Now, his gambit threatens to trigger a drive for his ouster.

On Wednesday, the 52-year-old Louisianan shrugged off that risk, saying he’d rather send bullets to Ukraine than American troops.

“You do the right thing and you let the chips fall where they may,” he said, noting that his son would attend the US Naval Academy in the fall.

Ever since Johnson leapfrogged over more senior Republicans to become speaker, he has faced the threat of overthrow. So it’s no surprise. But what is surprising is that his salvation may come from Democrats.

Representative Adam Smith, the plainspoken top Democrat on the House Armed Services Committee whose chief concern is global security, says he won’t vote to remove Johnson from the speakership.

“I’m not going to be coy about it,” Smith told Bloomberg Television’s “Balance of Power” on Wednesday. “It does not serve the interest of Congress or the country to remove the speaker at this point.”

None of this — up to and including the possible Democratic rescue — would have been expected six months ago when Johnson was simply a House member representing the northwest and western parts of Louisiana, a Republican stronghold save for some Democratic areas of Shreveport and other pockets.

Even as he faced the ouster threat, Johnson spent a recent weekend afternoon at his meticulously kept suburban home doing yard work and skimming debris from his backyard pool.

Tim Turner Jr., assistant chief of Benton Fire District #4, said he knows his next-door neighbor is having a rough time at work. So, he didn’t pry when they chatted in their yards that afternoon.

Turner asked if the drifting smoke from a small twig fire was bothering Johnson. The speaker — dealing with bigger fires in Washington — said it was no problem.

“I try my best not to talk to him about politics. He gets enough of that at work,” Turner said. “I know how he is, and what he stands for. I align with what he says.”

It was a shock, Turner recalled, to come home for lunch one day last fall to a security detail parked out front. That’s when he learned his neighbor had become second in the line of succession to the president.

Down the road, Shelly Horton, Jr., the Republican mayor of the Town of Benton, surmises that Johnson “is in a very tough spot” in Washington. It wouldn’t be a surprise, he added, if Johnson was ousted.

“That will be taken hard around here,” he said. “The feeling around here is he doesn’t back down from his values, even if it cost him his position.”

Not everyone is sympathetic to the speaker’s plight.

Theron Jackson, a former Shreveport city council member and the Black pastor of the Morning Star Missionary Baptist Church, recalls first encountering Johnson years ago when Johnson pressed him and other local officials to block a new strip club from opening downtown.

Johnson, a lawyer representing a church group, did not prevail “because his argument was largely moral — he could never make a real legal claim because nobody had violated the law,” Jackson said.

Jackson, who is an independent, said he doesn’t particularly see any downside to Johnson losing his speakership for many in Shreveport.

“We have not gotten any benefits in terms of policy,” he says. He ticks off a series of items that he says Johnson has opposed that “people in this district need to survive” — from resources for parents, to income and tax credits, and pandemic-related help.

“It’s hard to be sympathetic about the fleas that the dog gets for laying with other dogs with fleas,” Jackson said.

Several miles away, a request to tour the high school Johnson graduated in 1990 — Captain Shreve High — is denied. But a video screen flashes the school’s battle cry, as fitting in Washington as it is in Louisiana.

It also underscores the challenges their famous alum faces.

“Respect The Swamp,” the screen reads.

--With assistance from Kailey Leinz and Joe Mathieu.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.