Apr 24, 2024

Battle Over Startup Leaves Early Investor With No Equity, $2.6 Million Legal Bill

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When Denis Grosz invested in software startup Toptal LLC in 2012, he hoped the $1 million bet could one day make him a fortune.

Instead, it landed him on the receiving end of a lawsuit, leading to more than $2.6 million in damages against him and his new firm and possibly tens of millions more in legal fees.

At issue is a challenge to a fundamental convention in Silicon Valley: whether the startup has denied early investors a return by refusing to switch their decade-old convertible debt commitments into equity, tying up their holdings even as the company has flourished. Without equity, they can’t sell their interest in Toptal, making their outlay worth little more than the day they invested.

While Silicon Valley relationships between investors and the startups they fund are frequently tense, it’s rare for them to boil over into lawsuits. Deals are usually hashed out behind closed doors, struck by founders eager to please their backers and investors wanting to seem founder friendly.

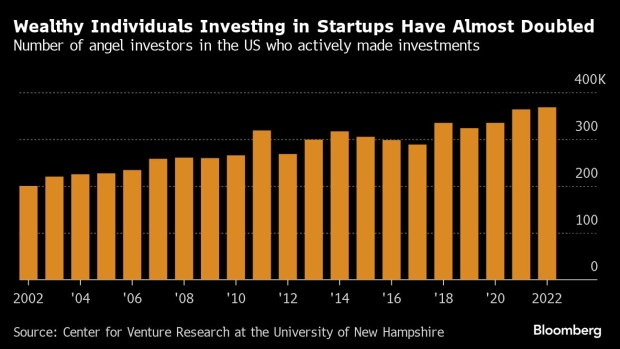

Lately, that dynamic has come under strain. As interest rates have climbed and investors have handed out less money, there’s more pressure on startups to eke out returns. At the same time, a greater number of startup investors are, essentially, amateurs — wealthy techies looking for somewhere to invest the money they’ve made over the last decade-plus of good times in the industry.

In Toptal’s case, its early investors — including Grosz — said the company’s founder, Taso Du Val, told them they’d get equity when Toptal converted from a limited liability company to a corporation, a transition that usually happens in the first year or two of a successful startup’s existence. But that still hasn’t happened, even though Toptal generates hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue.

In March 2020, Toptal sued Grosz and Mechanism Ventures — a company Grosz set up that had hired several Toptal executives and contractors — for breach of contract, business disparagement and civil conspiracy, among other claims. The suit accused Grosz of using Mechanism to “aggressively poach” employees, said he’d worked with others to damage Toptal and benefit himself, and claimed he’d done it while under contract as an adviser to Toptal.

A jury found Grosz liable for breach of contract and of good faith related to his position as an adviser, but not for business disparagement, intentional interference, defamation or the civil conspiracy claims. Mechanism was found liable for intentional interference, and to have acted with malice.

In affirmative defenses against Toptal, Grosz and Mechanism alleged fraud and breach of contract of his advisory agreement. Toptal was found not liable for either.

Toptal won a little over $16 million in damages in November, comprising awards of about $500,000 each against Grosz and Mechanism, and $15 million in punitive damages against Mechanism. On Monday, a judge lowered the punitive damages to $1.6 million. Grosz and Mechanism are expected to file appeals on the verdicts themselves, according to a document they filed in February in Nevada Supreme Court.

Toptal shows the investor-founder relationship at its worst, and could signal more disputes to come. While many investments are too small for venture firms to spend time recouping, that’s not always the case for individuals, said Margaret O’Mara, a University of Washington professor and Silicon Valley historian. The number of individuals making investments nearly doubled in the two decades leading up to 2022.

In cases like this, a different startup might attempt to mollify its backers, fulfilling Silicon Valley’s tradition of rewarding investors. Kickstarter, for example, gave investors including Union Square Ventures a dividend when it decided not to go public or sell.

In Toptal’s case, the players are smaller — except for early investor Andreessen Horowitz, a giant that can afford to lose its $100,000 investment. Grosz’s attempts to engage that firm in a discussion of how to pursue a return on Toptal were unsuccessful, emails that became part of the legal discovery show.

In a battle of small investor versus small company, “they’re not counterbalancing each other in terms of what they bring to the table,” said O’Mara. “They are not seasoned operators, deeply connected people with the deep Valley experience.”

Early Funding

Du Val started Toptal in 2010 as a 25-year-old high school dropout in Silicon Valley who’d already worked at Slide, a startup that was sold to Google. He developed what seemed at the time a novel idea: connecting companies with software engineers all over the world who could take on projects.

He raised early funding from Andreessen Horowitz and individuals like Ryan Rockefeller, and later raised $1 million more from Grosz. Grosz’s investments came in the form of debt — a convertible note that converts to equity when a startup raises more cash. Grosz’s deal included rights to around 10% of the company after its first equity financing. But Grosz didn’t get his stake: Toptal never raised more equity, and a conversion never happened.

At the time, convertible notes were a widely used way for early startups to raise cash. Now, founders generally use a similar instrument known as a SAFE, or simple agreement for future equity.

Today, 10% of Toptal likely would be worth a lot more than $1 million. According to Du Val, Toptal had $270 million in revenue in 2022, the most recent audited numbers available. In his countersuit, Grosz estimated that Toptal could be valued at more than $1 billion.

Grosz could still see an equity conversion — Toptal raising more money would trigger one — but Du Val said in an interview that it doesn’t make sense, in part due to tax reasons, to pursue that now. Grosz has never asked for his money back, according to his countersuit. Toptal tried to pay it back with interest in March 2020, according to his and Toptal’s suits, but Grosz rejected the attempt.

Grosz declined to comment. Rockefeller and Andreessen Horowitz didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

‘Portfolio Defense’

When it became clear that Toptal’s high-profile investor, Andreessen, wasn’t going to help pursue a return, individual backers started looking for other options, according to emails shown in court.

In May 2019, Grosz presented a “portfolio defense” to an investment club he belonged to, according to an email shown in court, floating possibilities like starting a competing company, initiating a lawsuit or working with a journalist on an expose.

First, though, he considered finding a professional investor to fight for liquidity in exchange for a cut of early investors’ stakes. In an email presented in court, Grosz said that an associate had described the approach as “outsourcing the assholery.” After cooling on that idea, he and Rockefeller discussed what the latter dubbed in another court-documented email as the “cancer patient” strategy: weakening Toptal to the point where it would make sense for Du Val to sell it, forcing his hand in converting to a corporation. In court testimony, Grosz denied implementing a strategy by that name, and the jury found him not liable for civil conspiracy with Rockefeller and others.

Grosz also pitched “The Information” on an article about how Toptal had grown without handing out stock to employees, the court filings show. He hoped that bad press would help drive away customers or shame Du Val into action, according to an email shown in court. The Information declined to comment via a representative.

When the article ran in August 2019, it captured the attention of Silicon Valley. A #boycottToptal movement emerged, and jobseekers posted on Reddit saying they wouldn’t work there. In March 2020, Toptal sued Grosz in Nevada, where he lived at the time. Grosz countersued that June.

Du Val said in an interview that he’s still dealing with the fallout from the boycott, defusing an exchange on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum at Davos this January. He said that a man he was introduced to immediately commented “Oh, you’re the guy known for ripping off noteholders.”

Before the liabilities and damages awarded in November, the judge made an additional ruling in October on a pre-trial motion filed by Toptal: Grosz’s ability to demand any equity stake had expired when his convertible notes hit their maturity date in 2014. That ruling is under appeal by Grosz.

Not on trial was the issue of how to reward a startup’s modest growth. Toptal is doing fine as a successful-but-not-huge company; it may never go public, but it doesn’t really need to. That’s a pretty good outcome — just not for investors.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.