Mar 25, 2024

Egypt’s $50 Billion Rescue Betrays Depth of Its Economic Crisis

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When the news came, Hisham Nader quickly finished work and went home to deliver a message to his family.

An investment by the United Arab Emirates would be the largest in Egypt’s history. That paved the way for the country to float its currency and finally secure another deal with the International Monetary Fund. The economy was saved, the government declared.

Nader, 43, who works in accounting and drives for Uber on the side, had a different take: “Brace for harder days,” he told his wife.

Away from the official narrative, for many in Cairo the international intervention in recent weeks exceeding more than $50 billion lays bare just how far the biggest Arab nation has fallen. An economic crisis that has been building for years has now reached a tipping point with war next door in Gaza and heightened threats to stability in the Middle East.

Rather than the prospect of better times, the question for households is how much more pain can they endure after the currency was effectively devalued for the fourth time in two years. Inflation already forced Nader to cut consumption of food, outings, clothes and move his kids to cheaper schools.

“We’ve been there before, it’s never good,” Nader said as he pointed to a TV screen broadcasting a government press conference explaining the measures on March 6. “Give me one reason why I should celebrate this.”

President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi is banking on the latest package attracting foreign investors back to the country of 105 million people, which has seen an exodus of the capital it needs to finance its huge debt.

The UAE will invest $35 billion in real estate after acquiring development rights to a region on the Mediterranean coast. The IMF is lending $8 billion. The European Union promised $8.1 billion of aid, followed by the World Bank providing more than $6 billion.

But in Cairo there’s a sense the country has gone beyond full circle from the Arab Spring revolution in 2011, the hardship now broader and deeper.

Egypt Avoided an Economic Meltdown. What Next?: QuickTake

El-Sisi’s leadership has gone where previous governments wouldn’t dare, Egyptians say, reducing subsidies for things like bread and electricity. The Oil Ministry announced an increase in fuel prices at the end of last week, citing the measures to stabilize the economy including the currency devaluation.

The minimum wage for state workers is 6,000 Egyptian pounds ($128) a month and the majority of the population relies on a subsidy system covering some essential goods. Changes to spending habits, though, are also being forced on Egyptians who would have considered themselves relatively wealthy.

People have become more reliant on paying by instalments, not just for big-ticket items like furniture and appliances but for groceries, clothing and even at this year’s Cairo International Book Fair after publishers worried about sales.

Mona Ali, 27, an engineer at a multinational, had to scale back on café and restaurant outings, overseas trips and penny-pinch as she struggles to keep her bills paid. “I don’t have children and I used to kill myself at work just to enjoy a vacation abroad once a year or buy something nice for myself,” she said. “I now think about putting food on the table. Am I middle class anymore?”

Indeed, the most visible and ubiquitous signs of the economic malaise is on the dinner table, especially during the holy month of Ramadan when families traditionally break the daily fast with a feast.

Pulling her empty shopping cart past the carcasses dangling from hooks in the supermarket, Marwa Ahmed stops and points to a sign advertising local beef at 379 pounds a kilo. “We can barely afford lentils and vegetables, so meat is out of question,” said the 42-year-old mother of two.

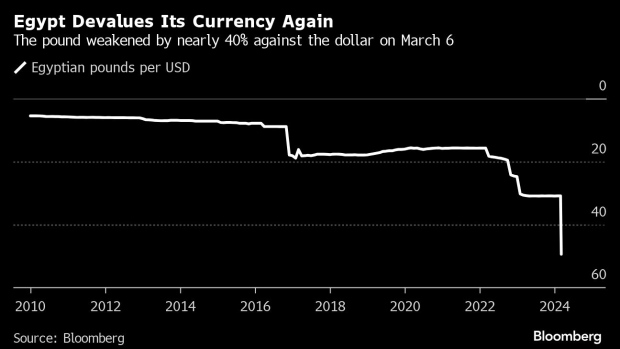

That was before the pound sank further on March 6 when Egypt stopped propping up its value, plunging about 40% to a record low of 50 per dollar within hours, having traded at about 30.90 for the past year.

Mohamed Qadry, a butcher from the southern province of Sohag last year started selling meat by grams and in downsized quantities. The smallest piece of red meat Qadry sells is 50 grams, for 37 pounds now.

“I have well-off customers like doctors who would send a kid or someone to buy half a kilo because they were embarrassed to buy in small amounts,” he said. “So I started selling meat in very small pieces.”

Inflation already had hit a record of over 35% in 2023. Key commodities such as sugar have nearly doubled in price, prompting the authorities to enact measures to avert what they say is price gouging by traders or distributors. The price of onions, whose traditional abundance in kitchens was a symbol of Egyptian culinary culture and an essential ingredient in street food like koshary have risen more than 400% in a year.

Inviting friends and family over for a meal isn’t something 34-year-old banker Sarah Hassan feels she can afford any more. “I used to have my house well-stocked at all time and especially ahead of Ramadan and I know that prices are going in just one direction — which is up,” she said. “But I can’t afford to buy more than my daily needs.”

El-Sisi’s re-election campaign late last year highlighted major symbols of his decade-long rule, from thousands of miles of roads and bridges to a Suez Canal expansion and new administrative capital east of Cairo. He points to security as success, how Egypt hasn’t become like other countries in the region and descended into chaos and war.

In an address to the public in January, he told Egyptians to bear with the economic pain as they were still able to eat and drink despite soaring prices. He defended the mega-projects, saying they provided millions of jobs.

El-Sisi, whose government allows little dissent, blamed the lack of foreign currency on Egypt’s decades-old dependency on imports, which he said required spending $1 billion a month on staples like wheat and vegetable oils and another $1 billion on fuel.

“I realize the extent of suffering and economic pressures in Egypt and I appreciate Egyptians’ resilience even more,” he said. “Don’t we eat? We eat. Won’t we drink? We drink, and everything is functioning. Things are expensive and some things are not available. So what?”

In an attempt to soften the impact on low-income families the government last month announced a 50% rise in the minimum wage for state workers. It was part of a wider social protection package that authorities say is worth some 180 billion pounds. That was before the pound was devalued again.

Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly said on March 18 that he expects people will see a drop in prices as more foreign currency becomes available, facilitating imports. The central bank said its increase in interest rates this month is meant to contain inflation.

The further drop in the value of the currency, though, means higher prices at least in the short term. Indeed, Egyptians know what to expect. The country devalued its currency by 48% and slashed subsidies at the end of 2016 to clinch a $12 billion IMF loan agreement, which helped repair the nation’s finances but spurred inflation.

Following the news this month, Ragab Mohamed rushed to the supermarket to buy groceries before prices shot up again. “This is the last straw,” said the 45-year-old accountant. “I don’t know how we’re going to survive this.”

Mohamed remembers having a good life some 15 years ago. He was married with two small children. Now, he works as an Uber driver and his wife is looking for a side job so they can afford university fees for those kids. They buy fruit and vegetables by individual piece rather than weight.

Ilham Mohamed, a 43-year-old teacher, said she tries to make do with the 15,000 pounds combined salary with her husband. Instead of buying 2 kilos of fresh meat a month for her small family of four, she now only consumes one kilo and uses every last morsel.

“I use cheap bones to make large amounts of broth that I can cook with for the rest of the month,” she said. “It’s a struggle, but I have to come up with all kinds of tricks to keep feeding my kids.”

Read this next: What Does the UAE Get for Its $35 Billion Investment in Egypt?

--With assistance from Michael Gunn and Tarek El-Tablawy.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.