Jan 30, 2024

Pimco Squares Up for a Bareknuckle Fight in Private Credit

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Pacific Investment Management Co. has been one of the loudest prophets of doom on private credit in recent months. Now it’s saying cracks in the red-hot asset class could appear as early as this year — and that it’s poised to use roughhouse tactics more common to hedge funds to grab bargains.

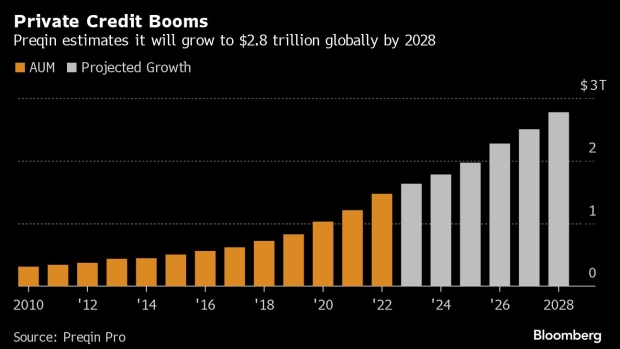

The investment giant has a history of making chunky contrarian bets going back to a money-spinning punt on cheap mortgage debt after the financial crisis. If it turns out to be right as the Cassandra of private credit, this booming $1.7 trillion market is about to go through a grueling reality check.

As fellow financial big guns such as Blackstone Inc. and Apollo Global Management Inc. have lined up to applaud a “golden moment” for private credit funds, which lend money directly to companies, Pimco has increasingly stationed itself on the other side of the wager. Executive committee member Christian Stracke predicts sharp drops in private loan values if base rates don’t fall quickly in 2024 and borrowers are crushed by their interest payments.

“We expect plenty based on what we’ve seen,” he tells Bloomberg. “We’re getting ready to pick up the pieces when and if there’s a shakeout.”

Whether he’s correct or not has implications that go way beyond the profits, or bragging rights, of wealthy financiers. Private credit funds have taken over much of the riskier corporate lending once done by investment banks, so any emerging distress in these loans could signal a deeper malaise in business. Insurers and pension funds have piled headlong into the asset class, too.

Pimco is also exploring options to use some of the bareknuckle methods of distressed investing — where funds buy into a struggling company’s debt and try to squeeze existing lenders — to shake up the more polite world of private credit, which usually prefers to resolve things behind closed doors. That threatens to expose direct lenders who’ve been valuing their loans too generously, a source of growing anxiety for financial regulators.

The firm sparked uproar a couple of years back when it and a bunch of funds threw a $1 billion lifeline to ailing hospital staffer Envision Healthcare. The emergency refinancing, like Pimco’s later involvement in aerospace supplier Incora, left other lenders out in the cold and cemented a trend in distressed investing for so-called “creditor on creditor violence.”

Stracke, who oversees Pimco’s operations outside the Americas and its credit research arm, says it’s looking at targeting private credit by dealing directly with a company’s private equity backer or negotiating “super senior loans.” Such moves often disadvantage other creditors, as with Envision and Incora.

How Private Credit Gives Banks a Run for Their Money: Quicktake

Bad Omens

This hunt for any emerging problems in private credit-backed companies is part of a broader sense at Pimco that while the US economy has been robust, it may slow this year, and that Europe and the UK could be headed for a hard landing. That would strain riskier assets. Chief Executive Officer Manny Roman was speaking about downturn opportunities as far back as 2018.

“There’s been a lot of talk from some managers for a while about the rise of distress in private markets, but it hasn’t yet played out,” says Gianluca Lorenzon of risk advisory firm Validus. “These managers have been waiting in the long grass, but the grass has been cut a few times now.”

Chris Alwine, global head of credit at Vanguard, another asset-management behemoth, did warn last week about a second-half recession in the US that would hit corporate debt, though he didn’t foresee many outright defaults in public markets.

Private credit is attracting the attention of bargain hunters because the loans are rarely traded, meaning any drop in their value might not be immediately obvious to outsiders. Direct lenders also typically charge a floating interest rate linked to central bank rates so many borrowers are carrying the burden of much heftier interest costs than they’d expected.

“The market’s putting all of its chips on rates coming down quickly in 2024/2025,” says Stracke, and that private credit “will hum along just fine.”

A popular metric used for private assets, the “fixed charge coverage ratio,” shows how well a company can cover costs such as rent, utility bills and interest payments from its earnings. This is running at about one times on average right now, according to Stracke, meaning some businesses are barely covering expenses. If rates stay where they are, or fall only slightly, as many as a quarter of private credit portfolios will have difficulties, he estimates.

“We also expect private credit loans, particularly mid-market, to come under some stress this year,” says Isaac Poole of Oreana Portfolio Advisory Service, a large investor in private funds, adding that he expects some situations to even stretch “beyond” distress: “The growth in this asset in the liquidity boom during the pandemic is an area we’ve been very cautious on.”

Eric Jacobson, a fixed-income director at Morningstar Research Services LLC, agrees that it makes sense to take an opposing view when a market’s as overheated as this one. The “standard for good asset managers is to avoid chasing trends and making sales pitches promising investors nirvana with new fund launches,” he says, “but instead to look for areas where they see a lot more value, even if that value isn’t being seen by others.”

Life After Bill

Pimco has been known as a bond firm since the days when famed trader Bill Gross was running things, and was one of the first of its peers to get into the now popular business of “alternative” investments such as private capital and property. But its concerted push into this corner of finance really got going in 2016. Since then its alternative assets have risen from €30 billion ($32.5 billion) to $170 billion in the first half of 2023, according to Charles Graham, a senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. That gives it a lot of firepower.

Its distressed playbook has been paying off in some areas. In 2022 it scooped up billions of euros of buyout debt that underwriting banks couldn’t get rid of. In recent months it has begun selling some of this at a double-digit profit. It snapped up €600 million of debt backing the buyout of British grocer Morrisons in the mid to high 80s percentage range. Those loans are now being quoted in the high 90s cents on the euro, market participants say.

In private credit, though, it’s having to be more patient about an asset class that has roughly tripled in size since 2015 by gobbling up much of Wall Street’s leveraged-loan business. Even as regulators have woken up to warnings — some of them from Pimco — that private markets lack transparency and are far too illiquid, any sustained downturn or signs of real trouble are yet to materialize.

In addition, some of private credit’s leading lights say aggressive firms trying to muscle in won’t find it easy to win over flailing corporate borrowers.

“One of the key features of private debt is that we try to resolve the issue ourselves,” says Cecile Mayer-Levi at Tikehau Capital. “Ultimately we try to help companies and that’s why they like us. We can be flexible without a company incurring risk and having to go through formal processes. This is why I’m skeptical of anyone trying to maneuver like this.”

For its part, Pimco is hoping that some direct lenders will need a swift exit from souring loans because of pressure from their own creditors, including banks who’ve lent to them based on their portfolio’s overall value.

Sabrina Fox of Fox Legal Training, an expert on company loan documents, says top-tier private credit firms will have often allowed some wiggle room in lending terms as they competed for business, as they did during the previous leveraged-finance boom. That opens the door to Envision-type attacks. “There may be some protections around third party lenders,” she says. “But a lot of documents do allow for these lenders to move in.”

Interlopers also spy a chance to profit because private assets are usually valued at a fund managers’ discretion, and not constantly “marked to market” in the same way as publicly traded debt such as junk bonds and bank-provided leveraged loans. For Stracke, this means lending positions can fester if a fund manager isn’t getting outside cues, and loans can be mispriced.

“Mark to market can be a distraction,” he says. “But it can also be a healthy way of signaling potential disruptions and enabling the market to function.”

--With assistance from Davide Scigliuzzo.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.