Mar 28, 2024

How Altice Can Push Its Creditors to Cut Billions of Debt: Q&A

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Billionaire Patrick Drahi’s Altice is asking creditors to agree to losses as the company’s embattled French telecommunications arm pushes to slash a debt burden of almost €25 billion ($27 billion).

Altice France SA will be looking to cut the pile by as much as €10 billion, according to analyst estimates, with the group targeting leverage below 4-times earnings, from the current 6.4 times.

The extent of the losses creditors will carry won’t only hinge on the money raised through the sale of assets, but also whether the proceeds will be taken into consideration at all.

Executives are proposing that debt holders accept a haircut in return for allowing the funds as part of a debt deal, arguing that the proceeds aren’t legally tied to Altice France’s liabilities.

Complicating matters further is an investigation in France and Portugal for alleged corruption, with Altice saying it’s a victim of the alleged wrongdoing.

In another blow, Moody’s Ratings cut Altice France’s credit rating to one of its lowest tiers on Wednesday.

Altice declined to comment on questions for this article.

1. Why does Altice want to reduce its debt now?

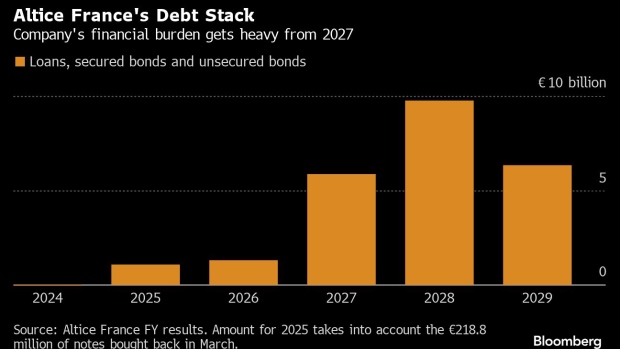

Investors and creditors were surprised by Altice’s aggressive opening salvo over the fate of the company’s debt load. It faces no liquidity squeeze in the near term, with a big maturity wall starting in 2027.

With a $60 billion debt-pile across three business in the US and Europe, Drahi has told creditors previously that anything and everything was up for sale.

Deleveraging would boost the valuations of debt-ridden businesses such as XpFibre and ailing telecom operator SFR, creating equity value for Drahi at the expense of his creditors.

In anticipating Altice’s next step to win sufficient support for its debt-cutting plan, creditors may want to look at how similar situations have played out in recent times.

Read more: Billionaire Drahi Cornered by Debt Mountain, Corruption Scandal

2. Can Altice follow a US-playbook?

One option is for Altice France to follow a US-style liability management exercise, given that its debt is governed by New York law.

In these situations, companies will typically reach a deal with a section of its creditors on terms that are detrimental to others, a tactic popularly known as creditor-on-creditor violence. These maneuvers are seen as aggressive and often trigger litigation.

A well-known type of LME is known as “drop-down,” where a company moves an asset out of creditors’ reach and uses it to raise more debt, typically with more protection than the existing liabilities.

This leaves original creditors with a smaller pool of assets to recover their investment if things go wrong. A classic example is that of retailer J-Crew, which removed its intellectual property rights away from creditors.

Another popular type is “up-tiering,” or priming. In this case, some creditors are given more security than others in the same box.

In such a scenario, participating creditors will provide incremental financing, which allows them to move up the repayment line. Creditors that don’t agree to the transaction could be stripped of some covenants.

Mattress maker Serta Simmons Bedding LLC and aircraft parts manufacturer Incora are recent examples of this.

3. Have aggressive tactics worked in Europe?

Few have tried, and even fewer have succeeded in following such tactics in Europe.

There are many possible reasons: Directors duties are more restrictive than in the US, other legal tools can provide a more certain outcome, while a smaller market means there’s less room for back-stabbing among creditors.

One instance in which such tactics did work was the case of Greek gaming operator Intralot SA. In 2021, the firm agreed with holders of one of its bonds to replace their debt with new notes issued out of its US subsidiary — leading the remaining bondholders to lose their direct claim on the group’s biggest money maker.

There are more examples of failures: Luxury carmaker McLaren ended up asking shareholders for funding while giving debt holders stronger covenants. Furniture maker Keter is set to be taken over by creditors.

Read more: Europe Too ‘Polite’ for Firms to Stir Creditor-on-Creditor Chaos

Outside of creditor-on-creditor violence, two prominent cases of aggressive discounted buybacks were both conducted by LetterOne, for its Spanish grocer DIA in 2020 and UK health retailer Holland & Barrett in 2022.

LetterOne’s trump card was that if it bought back enough of the debt it would obtain the necessary majorities to change the terms at will. This meant that creditors which didn’t tender would’ve been stuck in a structure in which they had no negotiating power.

4. What about a French solution?

French carehome operator Orpea SA and grocer Casino Guichard Perrachon SA are the two largest groups that have used a combination of processes known as conciliation and accelerated safeguard to cram-down dissenting creditors, since the insolvency regime was introduced in 2021.

Most creditors involved in those reorganizations still have unpleasant memories of the process. That’s because debtors in France enjoy more negotiating power and protection than in other jurisdictions.

Conciliation sets a four-month timeline, which can be extended by one month, during which a company will be looking to reach a deal with a majority of secured debt holders.

Read more: Secretive French Restructuring Tool Is on Rise as Firms Struggle

After an agreement is secured, an accelerated safeguard is opened to get court approval. Junior holders aren’t allowed to claim anything before dissenting senior creditors get fully repaid.

Drahi would run the risk of losing control over the company if Altice France chooses to follow this route and secured creditors get impaired, unless he provided a big enough equity check.

Adding another layer of complexity is the fact that Drahi controls the French operations through a web of entities. Altice France Holding is a Luxembourg-based company, so the restructuring could involve a cross-border process.

--With assistance from Giulia Morpurgo and Reshmi Basu.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.