Jul 2, 2019

Lee Iacocca, star CEO who led Ford, saved Chrysler, has died

, Bloomberg News

Lee Iacocca, the U.S. auto executive and television pitchman whose feel for consumers’ changing tastes helped produce the Ford Mustang and the Chrysler minivan and made him one of the first celebrity CEOs, has died. He was 94.

His death was reported by his family, according to the Washington Post.

Studied in business schools, emulated by a generation of executives, Iacocca was a star salesman for cars and for himself, spurring periodic talk of running for president. (He never did.) His autobiography was by far the top-selling hardcover nonfiction book of 1984 and 1985, according to the New York Times. For more than three decades, since his appointment by President Ronald Reagan, he led the effort that has raised more than US$700 million to restore the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

Iacocca “will probably go down in history as the first modern example of a charismatic business leader,” Harvard Business School professor Rakesh Khurana wrote in 2002. Iacocca’s turnaround of Detroit-based Chrysler Corp. “made him a celebrity and even a national hero,” one who relied on an “inspirational leadership” style that presaged that of Apple Inc.’s Steve Jobs, among others, he said.

Besieged Carmakers

Iacocca was no miracle worker, however, and the American auto industry’s struggles didn’t end with his tenure. Japanese carmakers saw their U.S. market share grow 10-fold, to about 30 per cent, during his 23 years leading two of America’s Big Three automakers. Chrysler, which averted collapse in 1980 in what may have been Iacocca’s crowning achievement, was buffeted by the financial crisis and recession of 2008, filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2009.

“It pains me to see my old company, which has meant so much to America, on the ropes,” Iacocca told Newsweek at the time. The company emerged as Chrysler Group LLC, majority-owned by Italy’s Fiat SpA. It is now named Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV.

Iacocca first came to prominence when, at 36, he was named general manager of Ford Motor Co.’s flagship Ford division in 1960. With a group of like-minded young executives, he formed what became known as the Fairlane Committee — named for the inn where they met for brainstorming dinners — to discuss how to design a low-cost, sporty car that would entice younger, more affluent families to become two-car households.

“It had to be a sports car but more than a sports car,” Iacocca wrote in his memoir. “We wanted to develop a car that you could drive to the country club on Friday night, to the drag strip on Saturday and to church on Sunday.”

Mustang Fever

The Mustang, introduced at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, was an unqualified hit. Iacocca and the car appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek, with Time calling him “the hottest young man in Detroit.” As for the car itself, Time swooned: “Priced as low as US$2,368 and able to accommodate a small family in its four seats, the Mustang seems destined to be a sort of Model A of sports cars, for the masses as well as the buffs.”

Ford sold more than 400,000 Mustangs during the first model year. The car’s styling captured young buyers, and Mustang clubs sprang up around the country.

Not everybody believed Iacocca deserved the share of credit he got.

“The model was totally completed by the time Lee saw it,” Eugene Bordinat Jr., Ford’s design director at the time, told Time in 1985. “We conceived the car, and he pimped it after it was born.”

Sparring Executives

Iacocca became president of Dearborn, Michigan-based Ford in 1970. At 46, he was second in command only to Chairman Henry Ford II, grandson of the company’s founder and seven years his senior. During Iacocca’s eight-year tenure, the two men sparred over topics big and small, from car design to perceived personal slights.

Executive-suite reorganizations in 1977 and 1978 resulted in de facto demotions of Iacocca and led to a showdown meeting on July 13, 1978, at which Ford ordered him to resign. His last day on the payroll was Oct. 15, his 54th birthday. He had been at Ford for 32 years.

Years later, Iacocca devoted 40 pages in his autobiography to settling the score.

He called Henry Ford II “evil,” a “spoiled brat” who was “always on the lookout for palace revolts” and cared only for “wine, women and song.” Iacocca said that when he pressed Ford for a reason for his dismissal, Ford replied, “Well, sometimes you just don’t like somebody.”

Iacocca’s ‘Arrogance’

Ford, who chose not to respond publicly to Iacocca’s book, “never warmed to Iacocca” and “disliked his arrogance, brashness and vanity,” David Lewis, a University of Michigan professor, wrote in “100 Years of Ford” (2003).

In a 1982 interview with Lewis, Ford faulted Iacocca’s vision.

“He got thoroughly confused in his later years by what the hell to do,” Ford said. “He had a new program every two or three months. The organization was totally discombobulated.” The transcripts of Ford’s interviews with Lewis were sealed, at Ford’s insistence, until 1992, five years after Ford’s death.

Two weeks after his ouster from Ford, Iacocca took over as president and chief operating officer at Chrysler, brought on by Chairman John Riccardo just as the company reported a quarterly loss of $160 million, its largest at the time.

“I really didn’t want to retire at 54,” Iacocca said at a press conference. “I really didn’t want to be banished from the auto scene.”

Second Chance

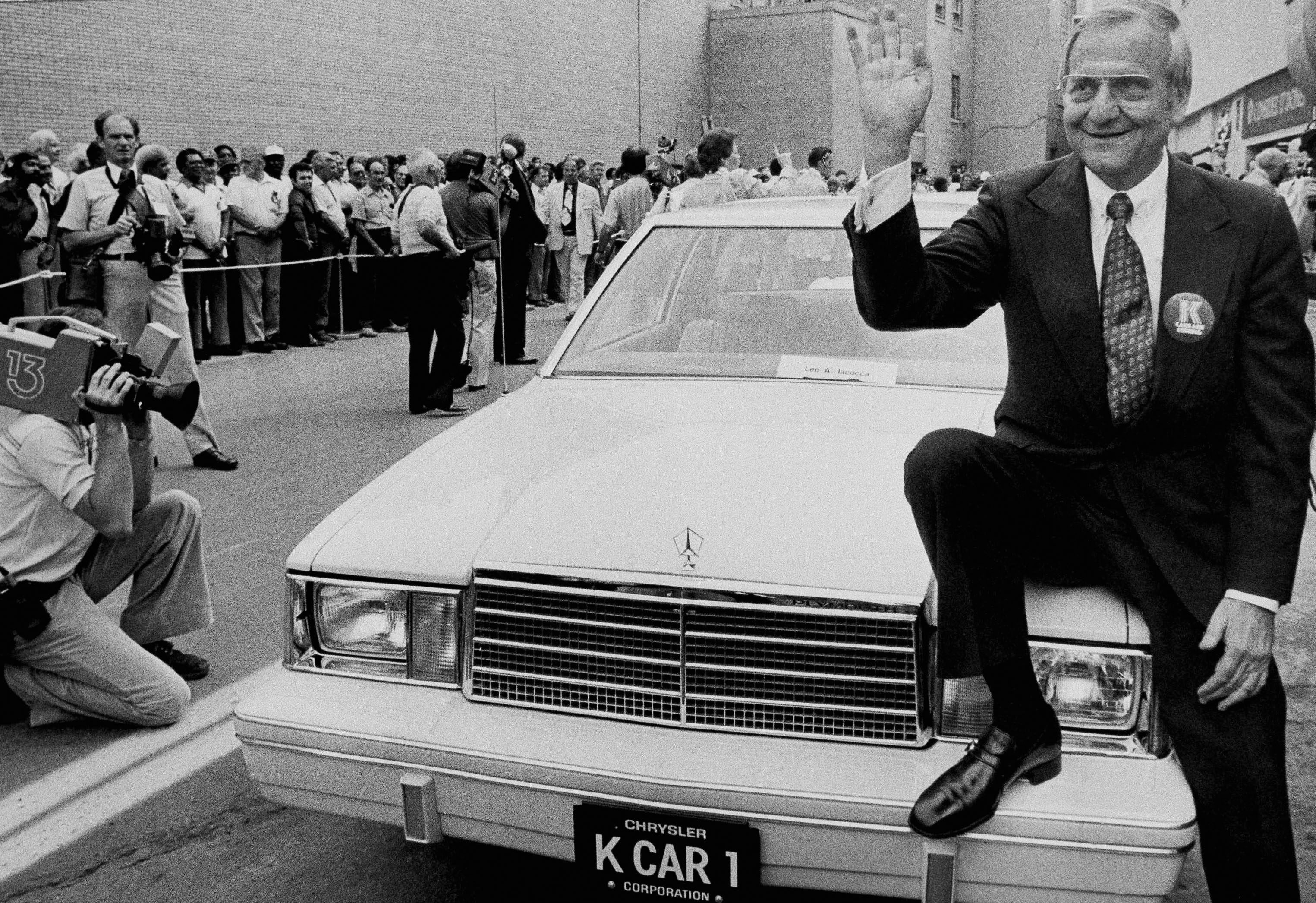

His 14 years at Chrysler gave Iacocca the chance to pursue initiatives that had met resistance at Ford. These included the fuel-efficient K-series Dodge Aries and Plymouth Reliant models as well as the first U.S.-produced minivan, introduced in 1983 as the Plymouth Voyager and Dodge Caravan. He steered Chrysler’s 1987 acquisition of American Motors Corp., with its Jeep franchise.

First, though, Iacocca had to save Chrysler from looming bankruptcy.

After becoming chairman and CEO in September 1979, he led a cost-cutting program that closed plants and slashed tens of thousands of jobs. He also sealed Chrysler’s deal with Congress and President Jimmy Carter’s administration for $1.5 billion in federal loan guarantees, a rare government intervention in the marketplace that folk singer Tom Paxton enshrined in tune:

“I am changing my name to Chrysler,I am going down to Washington, D.C.I will tell some power brokerWhat they did for IacoccaWill be perfectly acceptable to me.”

In 1983, seven years earlier than required, Chrysler finished repaying the $1.2 billion in government-backed loans it had used.

On Television

As much as for any of his corporate decisions, Iacocca became known as the straight-talking, patriotic pitchman in Chrysler’s television commercials, produced by New York-based firm Kenyon & Eckhardt Inc., in which he vouched for Chrysler’s cars as superior to those from Japan and Germany.

“If you don’t agree they’re the best Chryslers ever made, the very best America has to offer at a sensible price, then I’m in the wrong business,” he said in one ad.

His trademark line went down in advertising history: “If you can find a better car, buy it.”

Lido Anthony Iacocca was born Oct. 15, 1924, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, the second child of Nicola Iacocca and the former Antoinette Perrotto.

Rheumatic Fever

His father had immigrated to the U.S. from San Marco, Italy, in 1902, and worked for almost two decades in Pennsylvania. He returned to Italy to get his mother, and while there, he met and married the 17-year-old daughter of a shoemaker. Back in Allentown with his wife and mother, he started a hot-dog restaurant, Orpheum Wiener House, which became regionally famous as Yocco’s. A daughter, Delma, was born, followed by their son.

Iacocca’s seven-month bout with rheumatic fever as he entered high school rendered him, four years later, ineligible to be drafted into World War II. He earned a degree in industrial engineering in 1945 from Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a master’s degree in mechanical engineering through a fellowship at Princeton University, then began work in 1946 at Ford.

After one year in engineering, Iacocca was granted a move to sales. In 1956, with his eastern Pennsylvania sales district lagging, he introduced the “56 for ’56” program, offering car buyers a new 1956 Ford for $56 a month for three years, with 20 per cent down.

Sales Soar

His district went from last place to first, selling an additional 75,000 cars, and Iacocca the car salesman was on his way to more senior positions at Ford. At 33, he became head of national car marketing.

Also in 1956, Iacocca married his longtime girlfriend, the former Mary McCleary, who had been a receptionist at Ford’s office in Philadelphia. They made their home in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and had two daughters, Kathryn Lisa Hentz and Lia Antoinette Nagy.

Putting his stamp on the Ford division after taking charge in 1960, Iacocca canceled U.S. release of the Cardinal, an inexpensive subcompact under development by Ford of Germany.

“It was a fine car for the European market,” he wrote in his memoir, but for Americans, “it was too small and had no trunk.”

Pinto Lawsuits

Following the success of the Mustang, he was given responsibility for planning and marketing all cars and trucks in the Ford and Lincoln-Mercury divisions.

The subcompact Pinto, introduced in 1971, was a blot on Ford’s record in the Iacocca era. A raft of lawsuits alleged that a flawed design made the car susceptible to fuel-tank fires if struck in a rear-end collision. Ford recalled 1.5 million of the cars in 1978.

At Chrysler, Iacocca stopped production of some large models to advance the fuel-efficient subcompact Dodge Omni and Plymouth Horizon. He assembled an inner circle filled with former Ford colleagues, including Harold Sperlich, head of new-car development, who had jumped to Chrysler a year before Iacocca did.

After helping to develop Chrysler’s K-car, Sperlich used its chassis and front-wheel-drive mechanics as the foundation for the minivan -- “Detroit’s most successful vehicle of the 80s,” Paul Ingrassia and Joseph B. White wrote in “Comeback: The Fall and Rise of the American Automobile Industry” (1994).

GM Takeover

By 1984, Iacocca was riding high. Chrysler’s profit that year was $2.4 billion, and Iacocca’s autobiography, co-written by William Novak, soared to No. 1 on the New York Times best-seller list weeks after its Oct. 15 release, with Bantam Books printing the millionth copy by mid-December. It spent 88 weeks on the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list.

By 1987, Chrysler’s footing was sturdy enough for Iacocca to consider taking over General Motors. He revealed in his second book, “Talking Straight” (1988), that he and Allied-Signal Inc. Chairman Edward Hennessy Jr. discussed a joint $40 billion hostile takeover of GM before abandoning the plan because of potential financing and legal complications.

“In the end,” he wrote, “I concluded that it might be easier to buy Greece.”

Iacocca stepped down on Jan. 1, 1993. His successor, Robert Eaton, would lead Chrysler into its $36 billion sale to Germany’s Daimler-Benz AG in 1998 -- a “merger of equals,” the companies called it -- to create DaimlerChrysler AG. Iacocca opposed the merger and said supporting Eaton was “one of the biggest mistakes I made in my life.”

Kerkorian Bid

When DaimlerChrysler sold Chrysler in 2007 to New York-based Cerberus Capital Management LP, Iacocca claimed validation for his point of view. “Daimler screwed Chrysler royally,” he wrote in Businessweek.

Iacocca’s involvement in billionaire Kirk Kerkorian’s unsuccessful hostile takeover bid for Chrysler in 2005 prompted the company to scrap plans to put his name on its new headquarters in Auburn Hills, Michigan. The rift was swiftly repaired when Iacocca returned to doing commercials for Chrysler, sharing the screen with actor Jason Alexander, rapper Snoop Dogg and an actress portraying his granddaughter.

Iacocca donated his fee for those commercials to the charitable foundation he founded to combat diabetes, the disease that claimed the life of his first wife in 1983.

Unwanted Headlines

His second marriage generated unflattering headlines. His bride, the former Peggy Johnson, was a onetime flight attendant, 26 years his junior, who had worked with him at the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. Married at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City in April 1986, they divorced in November 1987. Five years later, Iacocca won an annulment of their marriage, prompting Johnson to appear on television to describe her surprise and hurt. She died of a heart attack in 2000, at 49.

Iacocca’s third marriage, to the former Darrien Earle in 1991, also ended in divorce, in 1994.

Politically, Iacocca described himself as a Republican who had voted for presidential candidates of both parties. He endorsed Republican George W. Bush for president in 2000 and his Democratic challenger, Senator John Kerry, in 2004.

In his 2007 book with Catherine Whitney, “Where Have All the Leaders Gone?,” Iacocca urged voters looking ahead to the 2008 elections to “throw the bums out.” He said he had thought seriously about running for president in 1988 before deciding he wasn’t cut out for that particular chief executive post.

“You can be a success in business and not have the temperament to be president,” he wrote. “For myself, I concluded long ago that to run for president you’ve got to be overambitious or just plain crazy.”

--With assistance from Steven Gittelson.